Abstract

Research Article

The Bacteriological Profile of Nosocomial Infections at the Army Central Hospital of Brazzaville

Medard Amona*, Yolande Voumbo Matoumona Mavoungou, Hama Nemet Ondzotto, Benjamin Kokolo, Armel Itoua, Gilius Axel Aloumba and Pascal Ibata

Published: 25 November, 2025 | Volume 8 - Issue 1 | Pages: 009-022

Nosocomial infections are infections acquired during a stay in a healthcare facility, representing a major public health challenge worldwide, and particularly in Africa, due to their frequency, potential severity, and associated costs. In Congo, their epidemiological profile is not yet well understood.

It’s in this context that we undertook to conduct a retrospective descriptive study on nosocomial infections between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016, in the internal medicine department of the Army Central Hospital of Brazzaville, in order to analyze the bacteriological profile of nosocomial infections.

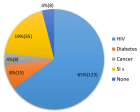

The study involved 189 patients. The results revealed that hospital-acquired infections were frequent, with a female predominance (71.43%), an average age of 32 years, and risk factors including self-medication with antibiotics (51%) and urinary catheterization (39%). Urinary tract infections were the most common (57%), with Escherichia coli as the main pathogen (17%), and mortality from these infections reached 53%.

The study highlighted a high mortality rate linked to hospital-acquired infections, primarily associated with HIV status and self-medication. Management, prevention, and infection control measures, including improved antibiotic stewardship, are necessary to reduce mortality.

Read Full Article HTML DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001032 Cite this Article Read Full Article PDF

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Infection Prevention and Control 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024.

- Carlet J. Healthcare-associated infections [Online]. Paris: High Council for Public Health (HCSP); 2002 [accessed 18 Sept. 2025]. Available from:https://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/Telecharger?NomFichier=ad382323.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Prevalence of nosocomial infections in 27 hospitals in 12 African countries: results of the WHO point prevalence survey, 2010. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010; 88 (10): 1070-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21226344/

- Durand-Zaleski I, Chaix C, Brun-Buisson C. The cost of healthcare-associated infections. Adsp. 2002; 38: 29-31.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Nosocomial infections: A major challenge for patient safety. World Health Organization Bulletin. 2021; 99 (11): 821-829.

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009 [accessed September 18, 2025]. 270 p. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906.

- College of University Professors of Infectious and Tropical Diseases (CMIT), publisher. ePILLY Trop 2022: Tropical Infectious Diseases [Online]. 2022 edition. Lyon: Alinéa Plus; 2022 [accessed 18 Sept 2025]. Available from: https://www.infectiologie.com/UserFiles/File/formation/epilly-trop/livre-epillytrop2022.pdf.

- Kankudja M, Tshibangu D. Epidemiological characteristics of patients in Lubumbashi. Rev Med Congo. 202; 45 (2):110-5.

- Bemba E, Koumeka PP, Ossale-Abacka KB, et al. Profile of respiratory diseases in the elderly in the pulmonology department of the Brazzaville University Hospital. Rev Mal Respir. 2018; 35 (4): 421-428.

- Moyen JM, Lobe I, Ndzeingou S, Koukouikila-Koussounda F. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and risk factors at the University Hospital Center of Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Pan Afr Med J. 2016; 24: 275. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.24.275.7626

- Nguefack T, et al. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and contributing factors in a hospital in the city of Douala. Pan African Medical Journal. 2016; 24: 275.

- Ouedraogo KM, Traore Y, Kologo JP, Ouattara A, Nikiema T, Ouattara S, et al. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and associated risk factors at Yalgado Ouédraogo Hospital in Burkina Faso. Pan Afr Med J. 2016; 24: 275.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Updated World AIDS Report 2022. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2022. 256 p.

- Kasongo Kakupa D, Kalenga Muenze P, Byl B, Dramaix Wilmet M. Prevalence and factors contributing to nosocomial infections in the city of Goma in the Democratic Republic of Congo: case of two referral hospitals CBCA-Virunga and Charité maternelle. J Med Public Health Policy Rep. 2024; 3 (2): 66-74.

- Kakupa DK, Muenze PK, Byl B, Wilmet MD. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and associated factors in the two university hospitals of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo: case of the University Clinics of Lubumbashi. Pan Afr Med J. 2016 Jul 27; 24 (275): 1-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.24.275.7626

- Mohamedi N, Batteux F, Larger E. Does diabetes really impair the immune system? Rev Med Interne 2019 Mar; 40 (3): 179-183.

- Vidal L, Ben dor I, Paul M, Eliakim-Raz N, Pokroy E, Soares-Weiser K, Leibovici L. Oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment for febrile neutropenia in cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD003992. Available from: 1002/14651858.CD003992.pub3.

- WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Study provides prevalence data and risk factors for nosocomial infections in hospitals within that region, noting the prevalence of risk factors like invasive devices. East Mediterranean Health J. 2010; 16 (10): 1070-8.

- Lorente L. Prevention of catheter-related infections: which catheter, which route and which insertion technique to choose? Intensive Care Medicine. 2012; 22 (S2):409-416.

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: key benchmarks [Online]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 Nov 17 [cited 2025 Sep 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- Ngoma A, Biyoya L. Antibiotic resistance in Brazzaville hospitals: prevalence and challenges. J Afr Health Sci. 2023; 45 (2): 112-9.

- Da L, Somé D, Yehouenou C, Somé C, Zoungrana J, Ouédraogo AS, Lienhardt C, Poda A. Current state of antibiotic resistance in sub-Saharan Africa. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2023; 2 (1): 3-12.

- Lebrun S, Sonda T, Dagnra C, Ngandjio A, Abotsi R, Akindele O, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Africa: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017 Sep 11; 72 (10): 2757-69.

- Saade D, Jabagi MJ, Bertrand M, Hider-Mlynarz K, Grimaldi L, Zureik M. Use of systemic fluoroquinolones in France between 2014 and 2023. Final report. EPI-PHARE; 2025 Jan 28.

- World Health Organization. Management of infectious complications associated with HIV infection - Recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

- Krir A, Dhraief S, Messadi AA, Thabet L. Bacteriological profile and antibiotic resistance of bacteria isolated in a burn intensive care unit over seven years. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2019; 32 (3): 197-202. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32313533/

- Dupont A, Martin B. Epidemiology of nosocomial infections: prevalence of Gram-negative bacilli. J Hosp Infect. 2023; 112 (5): 234-45.

- Bopaka RG. Nosocomial infection in the pulmonology department of the Brazzaville University Hospital. Rev Mal Respir Actual. 2021 Jan 10; 13 (1): 164.

- Ndalla AV, Moyen R, Obengui PK, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from wounds in Brazzaville (Congo). Pan Afr Med J. 2014; 18 (276).

- Otiobanda GF, Moyen E, Bomelefa-Bompay X, et al. Bacterial ecology of nosocomial infection in the intensive care unit of the Talangai District Hospital in Brazzaville. Pan Afr Med J. 2013 Apr 9; 14: 140. Available from: https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.14.140.1818

- Dahier F, Bomele RP, Mokondjimobe M, Nsonde-Offoumou RO, Moyen E. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and associated factors in the two university hospitals of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo: case of the University Clinics of Lubumbashi. Pan Afr Med J. 2016 Jul 27; 24: 275.

- World Health Organization. WHO warns of widespread resistance to common antibiotics worldwide [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025 Oct 13 [cited 2025 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news/item/13-10-2025-who-warns-of-widespread-resistance-to-common-antibiotics-worldwide.

- Trautmann M, Halder S, Hoegel J, Royer H, Haller M. Point-of-use water filtration reduces endemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections on a surgical intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Aug; 36 (6): 421-9.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RK, Fridkin SS, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Feb; 52 (3): 18-55.Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq146

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS): Implementation Manual [Online]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015 [cited 13 Nov 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/publications/i/item/9789241549400.

- Government of the Republic of Congo, Ministry of Public Health and Population. National Action Plan to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance in the Republic of Congo 2022. Brazzaville: Ministry of Public Health and Population; 2022.

- Pérez A, Dupont B. Mortality attributable to nosocomial infections in developed countries. Rev Infect Control. 2021; 45 (3): 112-9.

- Bouza E, Pérez MJ, Muñoz P, et al. Nosocomial bacteremia: clinical and microbiological epidemiology in a tertiary hospital over a 15-year period (1991-2005). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2007 Feb; 25 (2): 95-101.

- Niengo Outsouta G, Monkessa CM, Elombila M, Gallou Leyono-Mawandza PD, Ontsira Ngoyi EN, Tsouassa Wa Ngono GB, et al. Sepsis and septic shock in intensive care in Brazzaville (Congo). Health Sci Dis [Online]. 2022 Dec [cited 2025 Nov 13]; 24 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5281/hsd.v24i1.4135.

- Ossou-Ngui M, Ondzotto G, Moyen G, et al. Prognostic factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit at the Brazzaville University Hospital. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2010; 103 (4): 265-270.

- Ngassa L, Beka T. Mortality rate of nosocomial infections in intensive care in a hospital in Yaoundé. Pan Afr Med J 2018; 31 (1): 25-30.

- Ossibi Ibara BR, Obengui, Mbemba, Ahoui AC, Ontsira NG, Sekangué Obili G, Elenga Mbolla, Boumandouki P, Puruehnce MF. Causes of death among patients living with HIV in the Infectious Diseases Department of the University Hospital Center of Brazzaville. [Online]. 2014 [accessed 15 Oct 2025]; 7 (2): 5 pages. Available from: https://juniperpublishers.com/arr/pdf/ARR.MS.ID.555630.pdf.

- Ossibi Ibara BR. Neuromeningeal disorders during HIV in the infectious diseases department of the Brazzaville University Hospital: prevalence and factors associated with death. European Scientific Journal [Online]. 2016 [accessed 15 Sept 2025]; 12 (33): 177-88. Available from: https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/8326.

- Habonimana A, Gaturagi C, Nsabiyumva F, Iradukunda A. Diabetes and infectious complications: a study conducted at the Kamenge University Hospital Center on 36 cases. Med Afr Noire. 2021; 4 (9).

- MSD Manual. Septicemia and Infectious Shock [Online]. Merck & Co., Inc.; 2025 [accessed September 15, 2025]. Available from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/fr/professional/r%C3%A9animation/sepsis-et-choc-septique/sepsis-et-choc-septique.

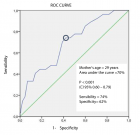

Figures:

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Similar Articles

-

Oral Candida colonization in HIV-infected patients: Species and antifungal susceptibility in Tripoli/LibyaEllabib M*,Mohamed H,Mokthar E,Ellabib M,El Magrahi H,Eshwika A. Oral Candida colonization in HIV-infected patients: Species and antifungal susceptibility in Tripoli/Libya . . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001001; 1: 001-008

-

Evaluation of novel culture media prepared from plant substrates for isolation and identification of Cryptococcus Neoformans Species ComplexEllabib M*,Krema ZA,Mokthar ES,El Magrahi HS,Eshwika A,Cogliati M. Evaluation of novel culture media prepared from plant substrates for isolation and identification of Cryptococcus Neoformans Species Complex. . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001002; 1: 009-013

-

Trypanosoma dionisii as an experimental model to study anti-Trypanosoma cruzi drugs: A comparative analysis with benznidazole, posaconazole and amiodaroneDe Souza W*,Barrias ES,Borges TR. Trypanosoma dionisii as an experimental model to study anti-Trypanosoma cruzi drugs: A comparative analysis with benznidazole, posaconazole and amiodarone. . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001003; 1: 014-023

-

A Review on filaricidal activity of phytochemical extracts against filariasis and the Parasites Genomic DiversityAM Gumel*,MM Dogara. A Review on filaricidal activity of phytochemical extracts against filariasis and the Parasites Genomic Diversity. . 2018 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001004; 1: 024-032

-

Host biomarkers for early diagnosis of infectious diseases: A comprehensive reviewArindam Chakraborty*,Singh Monica. Host biomarkers for early diagnosis of infectious diseases: A comprehensive review. . 2019 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001005; 2: 001-007

-

Virulence Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated at Suez Canal University Hospitals with Respect to the Site of Infection and Antimicrobial ResistanceNermine Elmaraghy*,Said Abbadi,Gehan Elhadidi,Asmaa Hashem,Asmaa Yousef. Virulence Genes in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Strains Isolated at Suez Canal University Hospitals with Respect to the Site of Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance. . 2019 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001006; 2: 008-019

-

Knowledge, perception and practices of Suez Canal University students regarding Hepatitis C Virus infection risk and means of preventionNermine Elmaraghy*,Hesham El-Sayed,Sohair Mehanna,Adel Hassan,Mahmoud Sheded,Maha Abdel-Fattah,Samar Elfiky,Nehal Lotfy,Zeinab Khadr. Knowledge, perception and practices of Suez Canal University students regarding Hepatitis C Virus infection risk and means of prevention. . 2019 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001007; 2: 020-027

-

in silico discovery of potential inhibitors against Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4: A major biological target of Type-2 diabetes mellitusNouman Rasool*,Andleeb Subhani,Waqar Hussain,Nadia Arif. in silico discovery of potential inhibitors against Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4: A major biological target of Type-2 diabetes mellitus. . 2020 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001008; 3: 001-010

-

Production and evaluation of enzyme-modified lighvan cheese using different levels of commercial enzymesMohammad B Habibi Najafi*,Mohammad Amin Miri. Production and evaluation of enzyme-modified lighvan cheese using different levels of commercial enzymes. . 2020 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001009; 3: 011-016

-

Development of ELISA based detection system against C. botulinum type BArti Sharma*,S Ponmariappan. Development of ELISA based detection system against C. botulinum type B. . 2020 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcmbt.1001010; 3: 017-020

Recently Viewed

-

Deep Learning-Powered Genetic Insights for Elite Swimming Performance: Integrating DNA Markers, Physiological Biometrics and Performance AnalyticsRahul Kathuria,Reeta Devi,Asadi Srinivasulu*. Deep Learning-Powered Genetic Insights for Elite Swimming Performance: Integrating DNA Markers, Physiological Biometrics and Performance Analytics. Int J Bone Marrow Res. 2025: doi: 10.29328/journal.ijbmr.1001020; 8: 006-015

-

Screening for Depressive Symptoms in Clinical and Nonclinical Youth: The Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2)Denise HM Bodden*,Yvonne Stikkelbroek,Daan Creemers,Sanne PA Rasing,Elien De Caluwe,Caroline Braet. Screening for Depressive Symptoms in Clinical and Nonclinical Youth: The Psychometric Properties of the Dutch Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2). Insights Depress Anxiety. 2025: doi: 10.29328/journal.ida.1001047; 9: 028-039

-

Stone on the Mesh: Intravesical Erosion after Laparoscopic Promontofixation-A Hidden Cost of DurabilityAyoub Mamad*,Mohammed Amine Bibat,Mohammed Amine Elafari,Midaoui Moncef,Amine Slaoui,Tarik Karmouni,Abdelatif Koutani,Khalid Elkhader. Stone on the Mesh: Intravesical Erosion after Laparoscopic Promontofixation-A Hidden Cost of Durability. J Clin Med Exp Images. 2026: doi: 10.29328/journal.jcmei.1001040; 10: 006-009

-

Obstructive Pyelonephritis Due to Postoperative Ureteral Stricture: A Case ReportAyoub Mamad*,Mohammed Amine Elafari,Mohammed Amine Bibat,Midaoui Moncef,Amine Slaoui,Tarik Karmouni,Abdelatif Koutani,Khalid Elkhader. Obstructive Pyelonephritis Due to Postoperative Ureteral Stricture: A Case Report. J Clin Med Exp Images. 2026: doi: 10.29328/journal.jcmei.1001039; 10: 003-005

-

Could metabolic risk factors contribute to the development of cervical cancer?Maydelín Frontela-Noda*,Eduardo Cabrera-Rode,Maite Hernández-Menéndez,Raquel Duran-Bornot. Could metabolic risk factors contribute to the development of cervical cancer?. Ann Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2019: doi: 10.29328/journal.acem.1001011; 3: 001-006

Most Viewed

-

Effects of dietary supplementation on progression to type 2 diabetes in subjects with prediabetes: a single center randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trialSathit Niramitmahapanya*,Preeyapat Chattieng,Tiersidh Nasomphan,Korbtham Sathirakul. Effects of dietary supplementation on progression to type 2 diabetes in subjects with prediabetes: a single center randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Ann Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2023 doi: 10.29328/journal.acem.1001026; 7: 00-007

-

Physical Performance in the Overweight/Obesity Children Evaluation and RehabilitationCristina Popescu, Mircea-Sebastian Șerbănescu, Gigi Calin*, Magdalena Rodica Trăistaru. Physical Performance in the Overweight/Obesity Children Evaluation and Rehabilitation. Ann Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acem.1001030; 8: 004-012

-

Hypercalcaemic Crisis Associated with Hyperthyroidism: A Rare and Challenging PresentationKarthik Baburaj*, Priya Thottiyil Nair, Abeed Hussain, Vimal MV. Hypercalcaemic Crisis Associated with Hyperthyroidism: A Rare and Challenging Presentation. Ann Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2024 doi: 10.29328/journal.acem.1001029; 8: 001-003

-

Exceptional cancer responders: A zone-to-goDaniel Gandia,Cecilia Suárez*. Exceptional cancer responders: A zone-to-go. Arch Cancer Sci Ther. 2023 doi: 10.29328/journal.acst.1001033; 7: 001-002

-

The benefits of biochemical bone markersSek Aksaranugraha*. The benefits of biochemical bone markers. Int J Bone Marrow Res. 2020 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijbmr.1001013; 3: 027-031

If you are already a member of our network and need to keep track of any developments regarding a question you have already submitted, click "take me to my Query."